Behind the Numbers: The Human Cost of Poverty Wages

Skilled Care, Poverty Pay

The Reality for Families

- Sleep deprivation: Many caregivers, like myself, monitor loved ones 24/7. My son Tom, who has Coffin–Siris Syndrome, hasn’t slept through the night in 24 years.

- Physical strain: Diapering adults, repositioning, lifting, and tube feeding demand constant strength and vigilance.

- Emotional toll: Isolation, burnout, and exhaustion are daily realities—yet we press on, because the alternative is institutionalization.

IHSS Training Proved Our Value

IHSS recently offered voluntary training courses that gave caregivers new tools to better manage seizures, dementia, diabetes, and advanced care needs. These courses were professional, engaging, and eagerly embraced. Most caregivers completed them—not only because they were paid for their time, but because we want to be better at what we do. The irony is stark: even as our skills and effectiveness increase, our wages are shrinking in real value year after year.Meanwhile, the demand for care is rapidly increasing. By 2030, one in four county residents will be over the age of 60. Without competitive wages to retain caregivers, the gap between those who need help and those able to provide it will only grow wider. Families will be left scrambling for support, and the county will face skyrocketing institutional care costs that far exceed the price of fairly compensating IHSS workers today.

Why This Matters to Everyone

When IHSS wages stagnate, families lose caregivers. People end up in group homes, nursing facilities, or hospitals—costing taxpayers 3–5 times more than in-home care. This is not just a caregiver issue—it’s a county budget issue, a healthcare issue, and a moral issue. What Needs to Change- Pay caregivers at least $22/hour now—still below the $23.12 living wage, but a critical step.

- Publicly recognize IHSS caregivers as part of the county’s Master Plan for Aging—no more exclusion from planning.

- Stop reinforcing the false narrative that IHSS is “low-skill.” Acknowledge caregiving as the essential profession it is.

The Bottom Line

Santa Barbara County cannot claim to support “aging in place” while ignoring the very workforce making it possible. Investing in IHSS caregivers is investing in dignity, fiscal responsibility, and the well-being of every resident.

Every supervisor knows that the county already spends far more when people are forced into institutions. Every taxpayer should know that underpaying caregivers today guarantees higher costs tomorrow. And every resident should know that a stable, skilled IHSS workforce is the only way thousands of our most vulnerable neighbors can remain safely at home, surrounded by family and community.

This is not charity—it is common sense. Caregivers are professionals who save lives, save money, and sustain families. The county must decide whether to continue a cycle of neglect and crisis, or to lead with foresight by raising wages and protecting the care system we all depend on.

More letters emailed to the Santa Barbara County Board of Supervisors

Padded Pockets, Empty Promises

I write to you not only as an IHSS caregiver, but as a lifelong resident of Santa Barbara County confronting a crisis in my own home. My 96-year-old mother-in-law has one final wish: to pass away in her own home, surrounded by family. Fulfilling this wish saves the county millions of dollars each year, and my children and I dedicate ourselves daily to making it possible.

Yet the reality behind this care is stark. Because she worked her entire career as a teacher without paying into Social Security, her only income is a pension of just $243 a month. My family covers her utilities, insurance, property taxes, medications, and every unexpected expense. I do this willingly—but it comes at a crushing cost. With your proposed wage, I cannot save for my own future. Instead of stability, the very program designed to support families like mine is pushing me closer to homelessness.

The irony is painful. In February 2025, this Board approved a 48.8% raise for itself, lifting your salaries from $115,000 to $171,000. That increase exceeded the cumulative rate of inflation since 2013 by more than 27%. In plain terms, you padded your own pockets well beyond what it would take just to keep pace with Santa Barbara’s cost of living. You made sure you would get ahead—while demanding that caregivers accept poverty as the status quo.

And this isn’t new. Every time we come to the bargaining table, the County plays the same game: raising our wage just enough to keep us locked about $10 below the living wage. That is not leadership—it is exploitation. You look out for yourselves, while deliberately leaving caregivers behind.

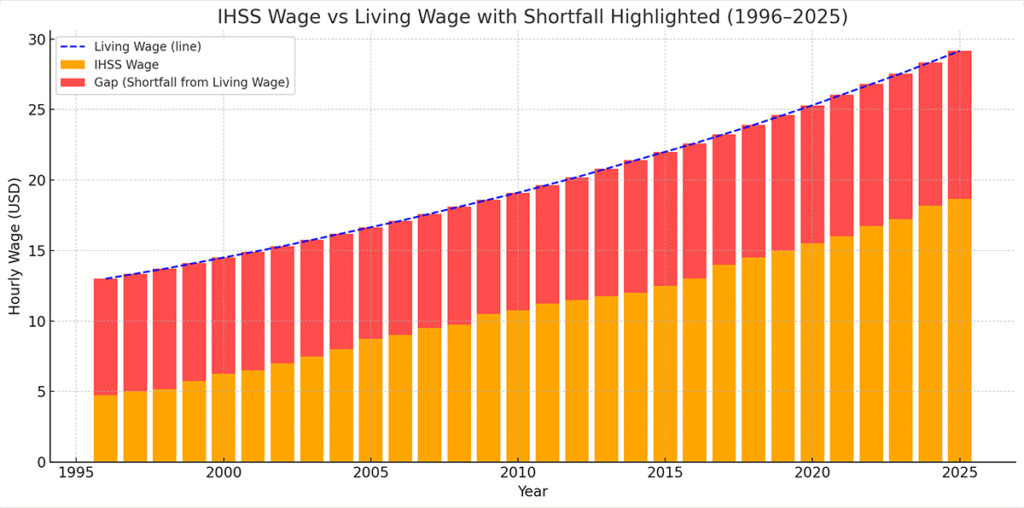

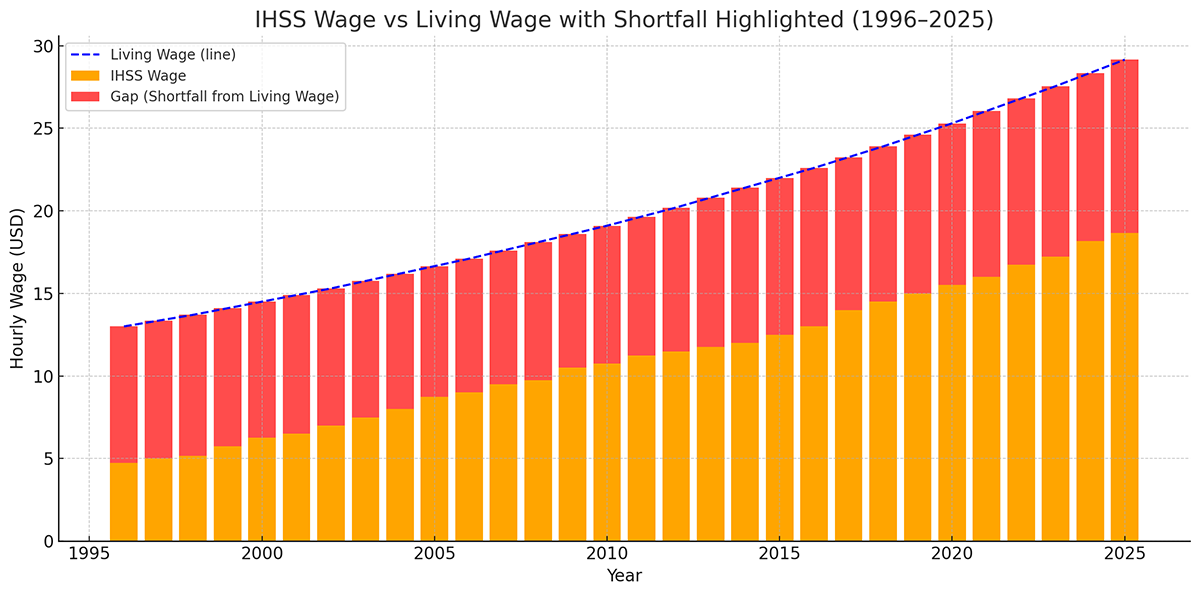

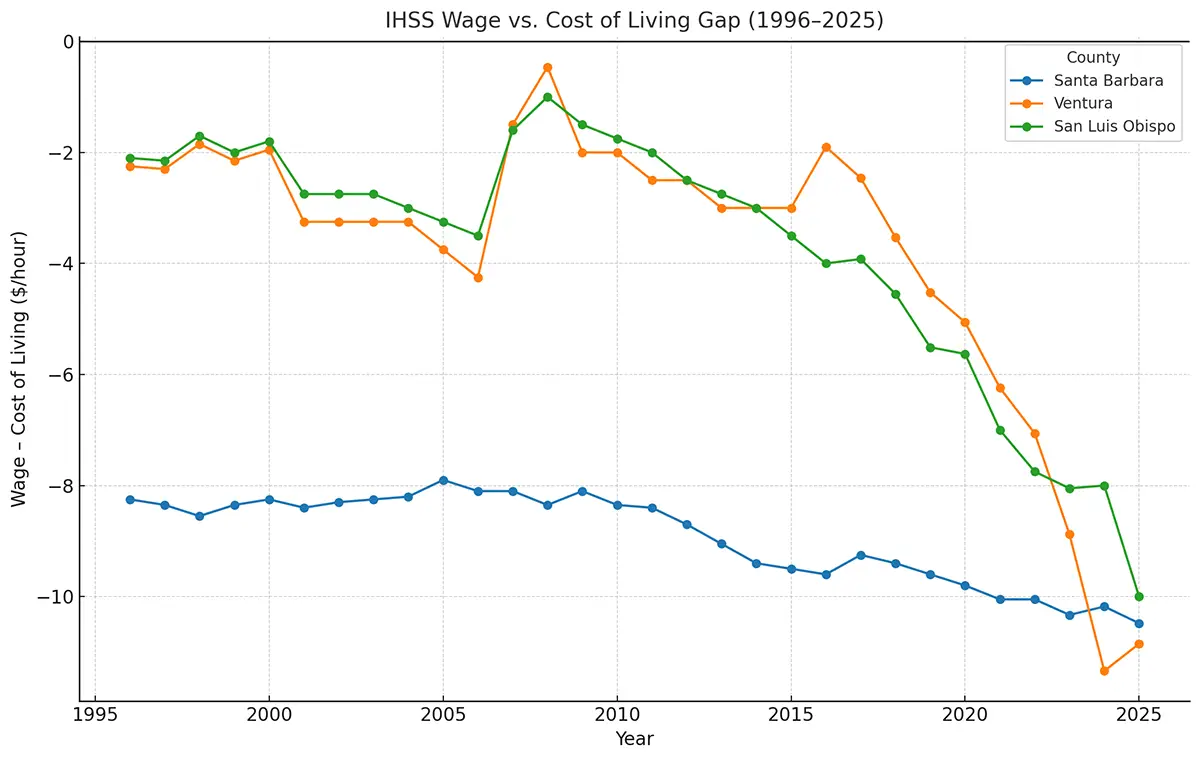

This is not about budget. It is about priorities. The numbers tell the story:

Wage Data Over Time

The pattern is undeniable: for nearly 30 years, IHSS wages in Santa Barbara County have never once kept pace with the cost of living. At best, they hover far below; at worst, they fall sharply behind.

- 1996 – IHSS wage: $4.75 vs. living wage $13.00 → 36% of living wage

- 2000 – IHSS wage: $6.25 vs. living wage $14.50 → 43% of living wage

- 2005 – IHSS wage: $8.75 vs. living wage $16.65 → 53% of living wage

- 2010 – IHSS wage: $10.75 vs. living wage $19.10 → 56% of living wage

- 2013 – IHSS wage: $11.75 vs. living wage $20.80 → 56% of living wage

- 2016 – IHSS wage: $13.00 vs. living wage $22.60 → 58% of living wage

- 2019 – IHSS wage: $15.00 vs. living wage $24.60 → 61% of living wage

- 2022 – IHSS wage: $16.75 vs. living wage $26.80 → 62% of living wage

- 2023 – IHSS wage: $17.22 vs. living wage $27.55 → 63% of living wage

- 2024 – IHSS wage: $18.17 vs. living wage $28.35 → 64% of living wage

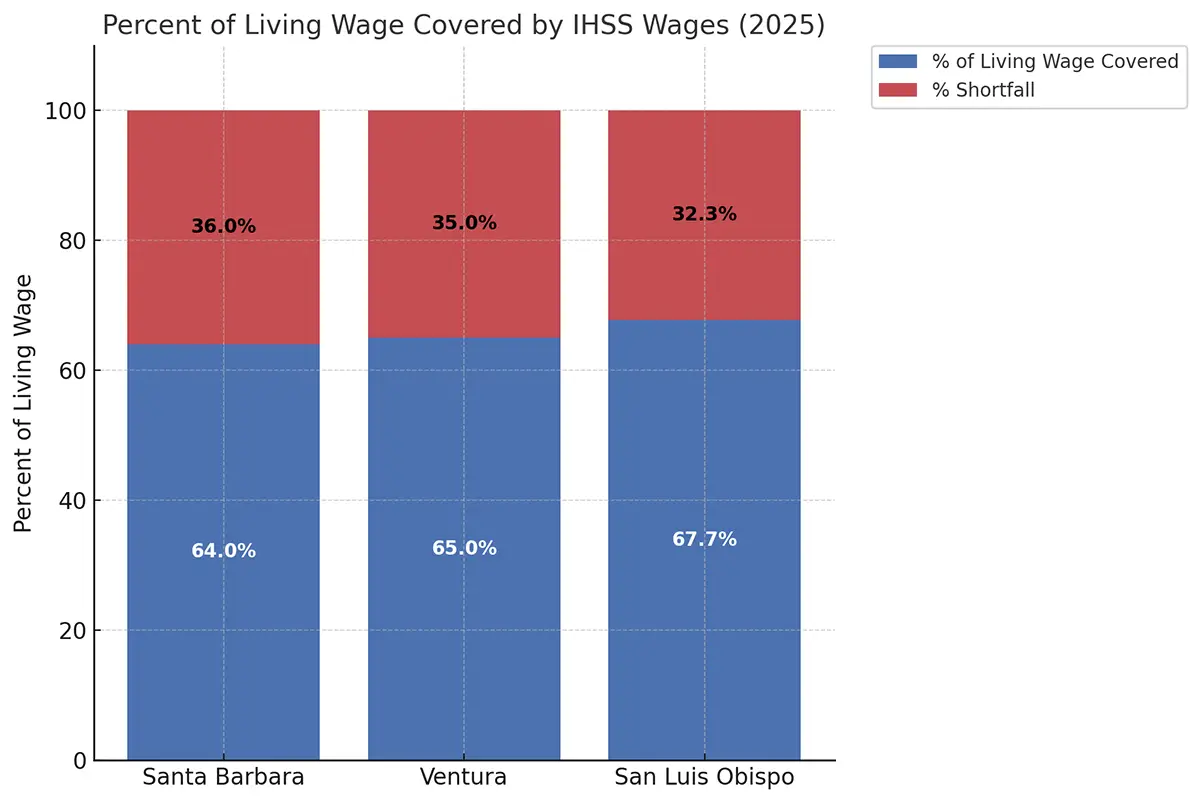

- 2025 (current) – IHSS wage: $18.67 vs. living wage $29.15 → 64% of living wage

Even when wages rise, they never reach the actual cost of living. The highest point we’ve ever hit was 64% of the living wage in 2024–2025. The lowest was 36% in 1996.

This is not progress. It’s a trap—one where caregivers are systematically denied stability no matter how the numbers shift.

You are asking me to provide life-sustaining care for your constituents while guaranteeing that my own life will remain unstable and my future uncertain. A living wage for IHSS caregivers is not a luxury; it is the only way to ensure that vulnerable residents of this county—like my mother-in-law—can remain safely at home, where they want to be.

I urge you to reconsider and to approve a contract that reflects both the dignity of the caregivers and the true value of the care we provide.

The Unseen Crisis: Why Low Wages Leave Our Most Vulnerable Without Care

I am writing to you again as an In-Home Supportive Services (IHSS) caregiver, but this time to highlight a critical consequence of our current wage crisis that is often overlooked: the impact on our most severely disabled residents. The IHSS program is designed to support individuals with a wide spectrum of needs, from basic assistance to complex, round-the-clock care. However, our current compensation structure fails to account for this reality, creating a system where the most vulnerable clients are left without a safety net.

The wage for an IHSS caregiver is a flat rate of $18.67 per hour, regardless of the level of care required. This means the pay is the same whether a caregiver is assisting with basic errands or managing a client with severe disabilities, such as frequent seizures, incontinence, sleep disorders, or self-harming behaviors. These complex cases demand a level of skill, physical stamina, and unwavering vigilance that is simply not reflected in the pay.

The result is a devastating market failure. Because the pay is the same, many of the limited available caregivers naturally gravitate toward less demanding cases. This leaves families like mine, who care for individuals with extensive and relentless needs, in a state of constant precarity. We are desperately in need of respite care or backup support, but there is no workforce available to fill these roles. The low wage has created a critical shortage, and the competition for employees is non-existent.

We are not advocating for a sliding scale of difficulty; we are advocating for a living wage that is attractive enough to create a competitive job market. A fair wage would attract a larger pool of qualified caregivers, allowing families with the most complex care needs to finally access the help they so desperately require. It would stabilize the entire system, ensuring that every IHSS recipient—regardless of their level of disability—has access to consistent and high-quality care.

I urge you to recognize that our current wage policy is not only unjust; it is actively endangering the most vulnerable members of our community. Please consider this critical point as you prepare to sign our contract. A significant wage increase is the only path to building a robust caregiver workforce that can meet the needs of all Santa Barbara County residents.

A Personal Story of Crisis and Care

I am writing to you today as a parent and an In-Home Supportive Services (IHSS) caregiver. My story is just one of many, but it illustrates the immense and often unseen challenges faced by those who provide care for our most vulnerable residents. It’s a story of love, dedication, and a relentless fight for my son’s well-being.

When my son Tom was born, he was born with unexpected challenges. He wouldn’t breathe, and two nurses had to carry him, racing down the hall to the NICU. After two weeks, he came home with a monitor for his heart and breathing. The breathing alarm never went off, but the bradycardia alarm, which signaled a dangerously low heart rate, went off again and again. I repeatedly raised this concern with his pediatrician, who eventually told me to take Tom to the ER.

We spent the next two and a half months in the PICU. Doctors discovered that Tom’s acid reflux was so severe that feeding him caused his heart rate to drop into the 20s. To a baby whose heart rate should be between 110 and 160, this was a life-threatening condition. To prevent heart failure, he underwent a Nissen fundoplication to block stomach acid and had a G-tube placed to bypass his esophagus for all feedings.

The G-tube was a nightmare. Tom howled if the food wasn’t at the perfect temperature, and any distress would cause the liquid to shoot out of the tube. This happened frequently, creating a messy and traumatic experience for both of us. At seven months old, Tom discovered the tube and pulled it out, creating a gaping hole in his abdomen. After he did this five or six more times, the ER staff trained me to replace the tube myself. The constant fear of infection and the stress of this procedure became a regular part of our lives.

When Tom turned one, he weighed only 12 pounds, while the average child his age weighs 24 to 26 pounds. His doctor explained that most children who still used a G-tube at this age would use one for the rest of their lives. I was terrified he would be dependent on it forever, and I was determined to improve his quality of life. I chose to wean him off the G-tube, even though it meant risking another surgery to re-insert it if I failed. I spent the next 10 months force-feeding him a special, high-calorie liquid that our insurance wouldn’t cover. After a year of intense effort, Tom weighed only 14 pounds, but he was finally eating on his own. We had succeeded in getting him off the G-tube, but it was a traumatizing and stressful time.

Valuing the Unseen Labor

My story is not unique among IHSS caregivers. We are not just changing diapers and providing special diets. We are managing complex medical needs, dealing with unexpected injuries and surgeries, and navigating a life of constant vigilance. Our work is emotionally gut-wrenching, physically demanding, and mentally exhausting.

While a typical job might offer promotions or public praise, IHSS caregivers often feel invisible and undervalued. We don’t get thanks or appreciation from anyone but the person we care for, if that. The only way you, as our elected leaders, have to demonstrate your respect and consideration for our work is through our wage.

Over the years, our wages have failed to keep pace with the cost of living. Your recent 48.8% salary increase, while IHSS wages are not even a living wage, sends a clear message of disparity. We are not just below the living wage; we are falling further and further behind with each three-year contract.

This is your opportunity to recognize the vital, life-sustaining work we do. It’s an opportunity to say thank you and to show that you value the caregivers who are the backbone of our community’s care system. It is time for our compensation to reflect the true value of this essential, professional work.

IHSS Wages Are Stagnant by Design

My name is Mary Bouldin, and I am a full-time IHSS caregiver for my adult son, Tom. I am writing to show you what the county’s wage policy really means for caregivers.

When you look at the numbers from 1996 to today, a pattern becomes undeniable:

In 1996, IHSS wages in Santa Barbara were $4.75/hour — the minimum wage at the time.

Since then, our wages have been renegotiated every three years, with each contract bringing a so-called “raise.”

But when those raises are compared to the actual cost of living, the result is always the same: by the end of the contract, our wages are worth almost exactly what they were at the beginning of the contract, once inflation is taken into account.

This means the raises are essentially meaningless. They are not lifting us closer to a livable income. They are simply maintaining the same low value we had decades ago.

IHSS wages are designed to lag permanently behind the cost of living. If the same policy continues, nothing will change in the future either — we will still be trapped at today’s low value, no matter what the contract says.

At the same time, this Board has chosen a different standard for itself. In 2023 you tied your salaries to the Consumer Price Index, and in 2025 you raised them nearly 50% in one vote by tying them to judicial pay. You secured for yourselves the very protections against stagnation that IHSS caregivers have been denied for decades. That contrast makes the county’s values painfully clear.

So I ask you: what is the purpose of these raises, if they never improve our situation? Why not be honest, skip the charade, and simply calculate the next contract wage by applying an inflation formula? The outcome would be exactly the same — except it would be clear to everyone that IHSS caregivers are not moving forward, not being rewarded for our labor, and not being valued for the essential service we provide.

Caregivers like myself work 140+ hours per week without days off, performing skilled labor that keeps vulnerable people out of institutions and saves the county millions of dollars. But caregivers cannot keep doing this if wages remain stagnant by design. When we are forced to leave caregiving behind in order to survive, the burden and cost will not disappear — it will fall back on the county in far more expensive ways.

There are both financial and emotional limits to living below the poverty line. What we have been able to do up to now does not mean we can continue indefinitely. You can only tread water for so long before you drown.

It is time to acknowledge that the current policy ensures caregivers will never advance. Raises that only preserve yesterday’s value are not real raises at all.

The Case for Fair Wages and Better Benefits for IHSS Caregivers in Santa Barbara County

I am writing to you today to draw your attention to the critical importance of a stable and well-compensated IHSS workforce, and to present evidence from a recent, authoritative report on the matter.

The California Department of Social Services (CDSS) recently commissioned a comprehensive analysis by the UC Berkeley Labor Center, titled “Analysis of the Potential Impacts of Statewide or Regional Collective Bargaining for In-Home Supportive Services Providers.” While this report focuses on statewide policy, its findings regarding caregiver retention, economic conditions, and client outcomes are directly relevant to the sustainability and quality of care provided by the IHSS program here in Santa Barbara County.

The report provides a clear, data-driven argument that investing in caregivers is a crucial strategy for improving the entire care system. Key findings demonstrate:

1. The Current Reality for Caregivers

The average IHSS wage in California is $18.13 per hour, which is significantly below the MIT-calculated living wage of $27.32 per hour for a single adult in the state. This disparity means that the median annual income for a full-time IHSS provider is around $23,000, which is less than half the state median for all workers. As a result, home care workers are twice as likely to live in poverty compared to other workers in California.

2. The Direct Link Between Pay and Retention

The report provides a clear link between fair compensation and caregiver retention. Higher wages are strongly correlated with reduced turnover, particularly for non-family caregivers, who had an annual turnover rate of 28.1% in 2023. This creates instability for care recipients.

- San Francisco Example: After union contracts increased wages, annual retention rose from 78% to 85% for all providers.

- Health Benefits: Providers with comprehensive health insurance are more likely to stay in their roles. In eight California counties with better health plans, retention measurably increased.

3. The Benefits of Investing in the IHSS Workforce

The benefits of improving caregiver compensation extend far beyond the individual worker. When a care provider has better job security and is not constantly stressed by economic instability, they can provide more stable and consistent care.

- Improved Client Outcomes: Stable provider-client relationships lead to a higher quality of care, which results in fewer hospitalizations, reduced falls, and higher patient satisfaction.

- Reduced Costs: A statewide $1 per hour wage increase could lower overall turnover by approximately 2 percentage points. While a wage increase has a fiscal cost, it also reduces expensive turnover and may lead to fewer costly nursing home placements.

- Economic Impact: Every $1 spent on IHSS pulls in $1.21 in federal Medicaid dollars and generates at least $2.42 in total economic benefit within California.

4. Lessons from Other States

Other states with statewide bargaining, such as Washington and Oregon, have higher base wages and offer more uniform benefits like paid time off and retirement contributions. These models demonstrate that it is possible to create a more robust and stable care workforce through a commitment to better compensation.

Our Request

Santa Barbara County faces a growing need for direct care workers. By advocating for and supporting policies that increase IHSS wages to a living wage and expand access to health benefits, you will not only be supporting the well-being of our essential caregivers but also ensuring a higher quality of life for our most vulnerable residents.

Mind the Gap

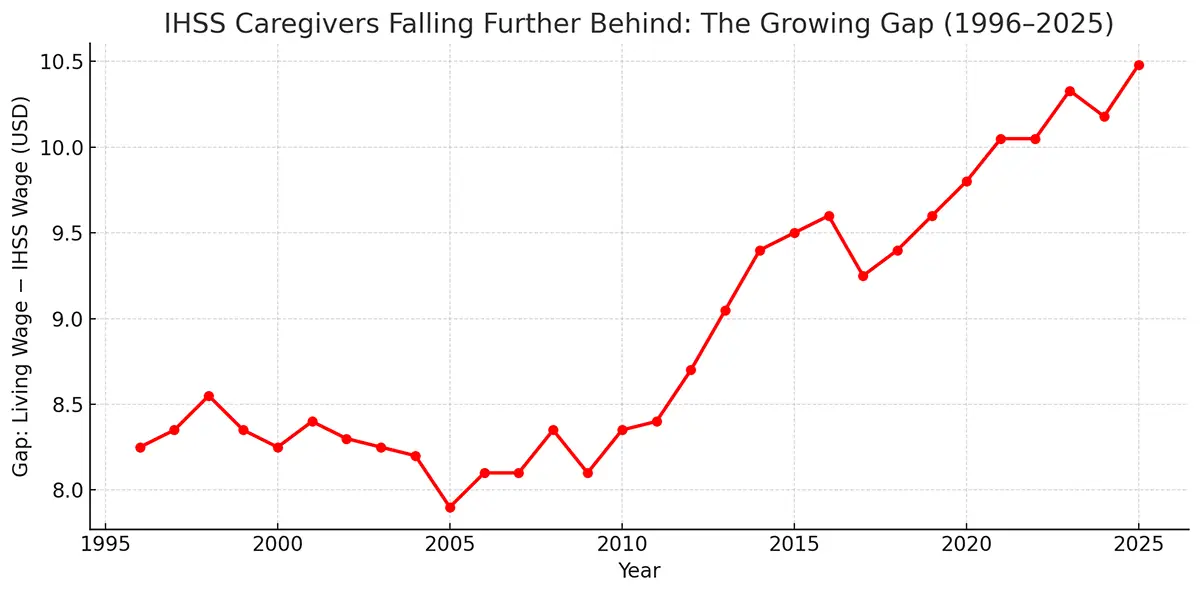

For decades, IHSS caregivers in Santa Barbara County have been trapped in the same cycle: every contract locks us into wages that fall well below the actual cost of living. I once thought it was a fixed $10 gap, but the reality is even worse: with each contract, we slip further behind. What was about an $8 shortfall in the 1990s has grown to more than $10 today, a steady erosion that ensures caregivers are less able to meet the cost of living with every passing decade.

Here are the numbers:

1996 — Caregivers earned $4.75 while the cost of living was $13.00.

Caregivers: $8.25 below a living wage.

1997 — Caregivers earned $5.00 while the cost of living was $13.35.

Caregivers: $8.35 below a living wage.

1998 — Caregivers earned $5.15 while the cost of living was $13.70.

Caregivers: $8.55 below a living wage.

1999 — Caregivers earned $5.75 while the cost of living was $14.10.

Caregivers: $8.35 below a living wage.

2000 — Caregivers earned $6.25 while the cost of living was $14.50.

Caregivers: $8.25 below a living wage.

2001 — Caregivers earned $6.50 while the cost of living was $14.90.

Caregivers: $8.40 below a living wage.

2002 — Caregivers earned $7.00 while the cost of living was $15.30.

Caregivers: $8.30 below a living wage.

2003 — Caregivers earned $7.50 while the cost of living was $15.75.

Caregivers: $8.25 below a living wage.

2004 — Caregivers earned $8.00 while the cost of living was $16.20.

Caregivers: $8.20 below a living wage.

2005 — Caregivers earned $8.75 while the cost of living was $16.65.

Caregivers: $7.90 below a living wage.

2006 — Caregivers earned $9.00 while the cost of living was $17.10.

Caregivers: $8.10 below a living wage.

2007 — Caregivers earned $9.50 while the cost of living was $17.60.

Caregivers: $8.10 below a living wage.

2008 — Caregivers earned $9.75 while the cost of living was $18.10.

Caregivers: $8.35 below a living wage.

2009 — Caregivers earned $10.50 while the cost of living was $18.60.

Caregivers: $8.10 below a living wage.

2010 — Caregivers earned $10.75 while the cost of living was $19.10.

Caregivers: $8.35 below a living wage.

2011 — Caregivers earned $11.25 while the cost of living was $19.65.

Caregivers: $8.40 below a living wage.

2012 — Caregivers earned $11.50 while the cost of living was $20.20.

Caregivers: $8.70 below a living wage.

2013 — Caregivers earned $11.75 while the cost of living was $20.80.

Caregivers: $9.05 below a living wage.

2014 — Caregivers earned $12.00 while the cost of living was $21.40.

Caregivers: $9.40 below a living wage.

2015 — Caregivers earned $12.50 while the cost of living was $22.00.

Caregivers: $9.50 below a living wage.

2016 — Caregivers earned $13.00 while the cost of living was $22.60.

Caregivers: $9.60 below a living wage.

2017 — Caregivers earned $14.00 while the cost of living was $23.25.

Caregivers: $9.25 below a living wage.

2018 — Caregivers earned $14.50 while the cost of living was $23.90.

Caregivers: $9.40 below a living wage.

2019 — Caregivers earned $15.00 while the cost of living was $24.60.

Caregivers: $9.60 below a living wage.

2020 — Caregivers earned $15.50 while the cost of living was $25.30.

Caregivers: $9.80 below a living wage.

2021 — Caregivers earned $16.00 while the cost of living was $26.05.

Caregivers: $10.05 below a living wage.

2022 — Caregivers earned $16.75 while the cost of living was $26.80.

Caregivers: $10.05 below a living wage.

2023 — Caregivers earned $17.22 while the cost of living was $27.55.

Caregivers: $10.33 below a living wage.

2024 — Caregivers earned $18.17 while the cost of living was $28.35.

Caregivers: $10.18 below a living wage.

2025 — Caregivers earned $18.67 while the cost of living was $29.15.

Caregivers: $10.48 below a living wage.

Every contract, the same story: wages rise just enough to make it look like progress, but always leave us about $10 behind. And it isn’t just that the gap exists—it is steadily growing. In 1996, caregivers were $8.25 below a living wage. By 2013, the shortfall had climbed past $9.00. Today, in 2025, caregivers are more than $10.40 behind. Each contract locks us deeper into poverty, ensuring that with every passing decade, the gap between what caregivers earn and what it actually takes to survive grows wider. After 30 years of this pattern, it’s impossible to call it anything but intentional.

And that’s the deeper injustice: every new contract pretends to move caregivers forward, but the numbers prove otherwise. Wages rise on paper, yet the shortfall against the cost of living quietly grows larger. What began as an $8 gap in the 1990s has expanded past $10 today. The pattern is unmistakable: instead of progress, each contract cements a deeper disparity.

This gap is not just about money. It’s about respect. Caregivers keep loved ones safe at home. We keep them out of institutions, saving the county millions of dollars every year. We do the difficult, intimate work that no one else is willing to do—and yet we are told that our labor, our health, and our futures are worth $10 less than what it takes to survive.

This isn’t sustainable. We cannot keep giving everything—our time, our health, our security—while receiving so little in return. At the very least, caregivers deserve wages that close the gap.

I urge you to raise the IHSS wage to at least $22/hour. A living wage is not a luxury—it is the minimum that allows us to keep doing this work without collapsing under the weight of it.

It’s time to stop pretending that raises mean progress when all they do is maintain the gap. Caregivers have been standing still for 30 years. You have the power to finally change that.

The Hidden Cost: My Family's Stability is Sacrificed for Your IHSS Savings

I am writing to you today not just as an IHSS caregiver, but as a daughter-in-law, a parent, and a Santa Barbara County resident facing a crisis of my own. Your decisions on IHSS wages have a direct and devastating impact on my family’s stability and future.

My 96-year-old mother-in-law has a single wish: to die in her own home, surrounded by her family. It’s a goal that saves the county millions of dollars annually, and one that my children and I work tirelessly to fulfill. Because her husband believed Social Security would fail, she did not pay into it as a teacher in the Goleta Union School District, and her pension is only $243 a month. As a result, my family has taken on the full financial burden of keeping her in her home.

This goes far beyond my IHSS hours. My children and I split the costs for utilities, her home insurance, and her property taxes. I cover her medications that aren’t covered by Cen-Cal, as well as every unexpected expense that arises. I bought her a new mattress, paid for safety bars in her bathroom, and purchased an Apple Watch with fall detection after a late-night fall left her bleeding and helpless. I buy the home necessities and manage the entire household, doing everything in my power to keep her safe and comfortable.

But what about my own safety and future? With my mother-in-law’s time being limited, I must now face the reality of my own living situation. The home she lives in will be inherited by her son, a hoarder. While he has offered to let my son and me stay, I cannot in good conscience remain in a home that would not pass a conservator’s annual inspection, putting us in an unsafe and legally precarious position.

With the current IHSS wages, I have no ability to save for our exit. I have no place to go, and your wage decisions have left me with no capability to remain anywhere in Santa Barbara County. The very system designed to support people like my mother-in-law and I is now forcing me into homelessness.

The county’s Master Plan for Aging, approved last month, calls for “Caregiving That Works” and highlights the need to support caregivers and address affordability. Yet, the current IHSS wage structure does the exact opposite. It exploits our dedication, it risks our health, and it puts our own housing and financial stability in jeopardy.

I urge you to look beyond the numbers and see the human cost of these policies. My family’s stability and future are on the line. A living wage for IHSS caregivers isn’t a luxury; it is a necessity that will allow us to continue providing the compassionate care your constituents depend on, and it’s what will ensure the caregivers themselves can afford to survive in this county.

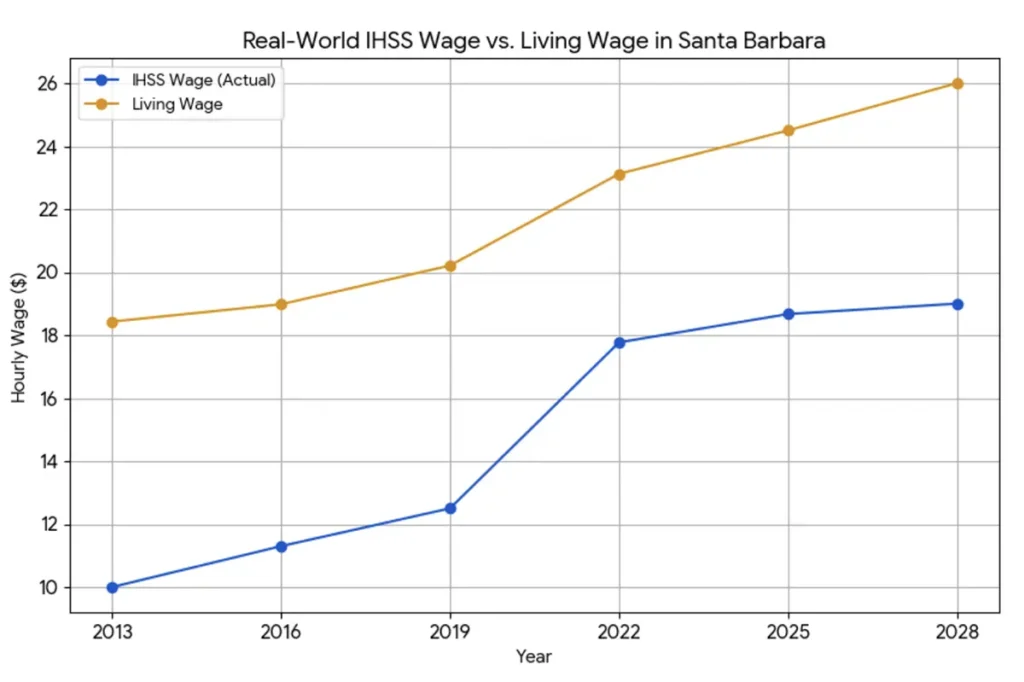

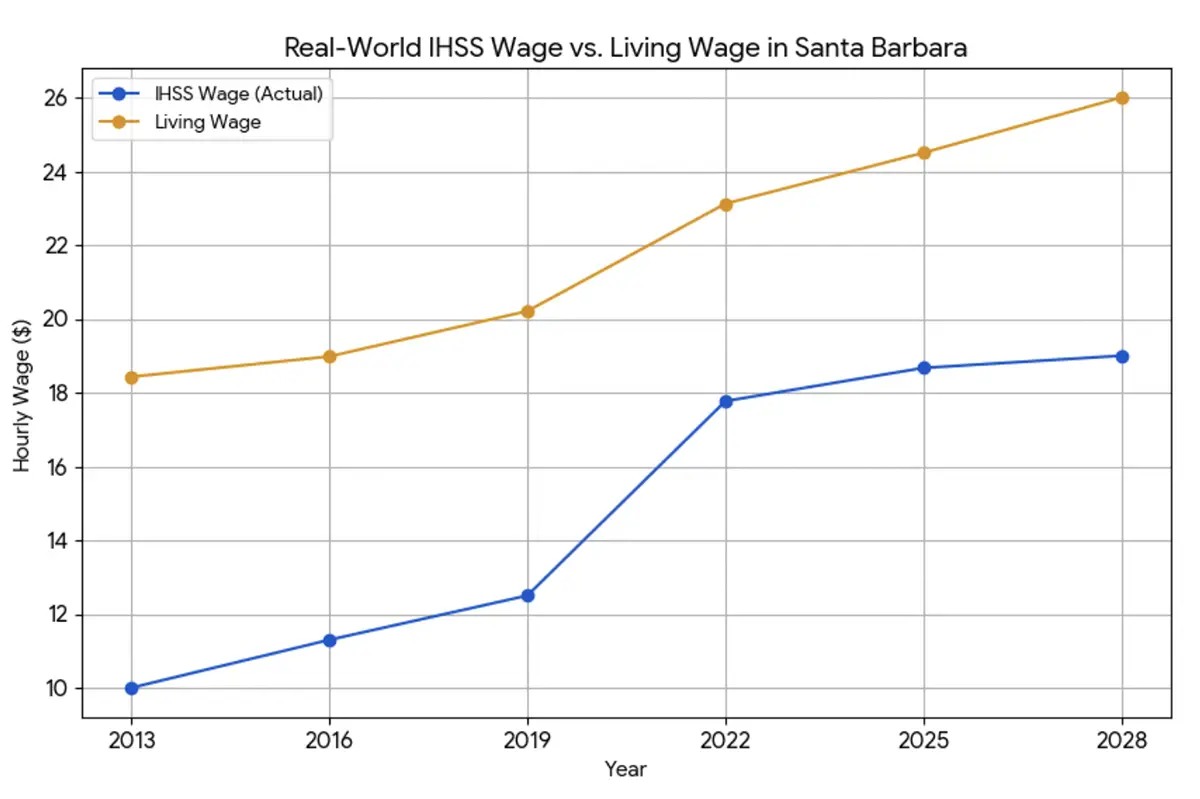

The Undeniable Truth: A Visual Case for a Living Wage

I am writing to you today not with a personal story, but with a plea based on the data of your own making. The charts below tell a story that no amount of rhetoric can deny: your decisions have created a system that is consistently and systematically devaluing the work of IHSS caregivers.

Chart 1: The Real-World Timeline

This chart shows the reality of our wages, including the impact of state-mandated minimum wage increases. It reveals three critical points:

- The State Saved Us: Our wages only saw a significant boost in 2022 when state law forced an increase, temporarily bringing our pay to 77% of the living wage.

- The Decline Has Begun: Since that high point, our pay has already fallen behind the cost of living. Your proposed new contract guarantees this decline will continue, with our pay dropping to 73% of the living wage by the end of the contract.

- The Stark Contrast: This chart also shows the stark reality of your own salaries. While our wages have been stagnant or in decline, you voted to give yourselves a 48.8% pay raise in 2025—an increase that was 27% more than was needed to keep up with inflation since 2013.

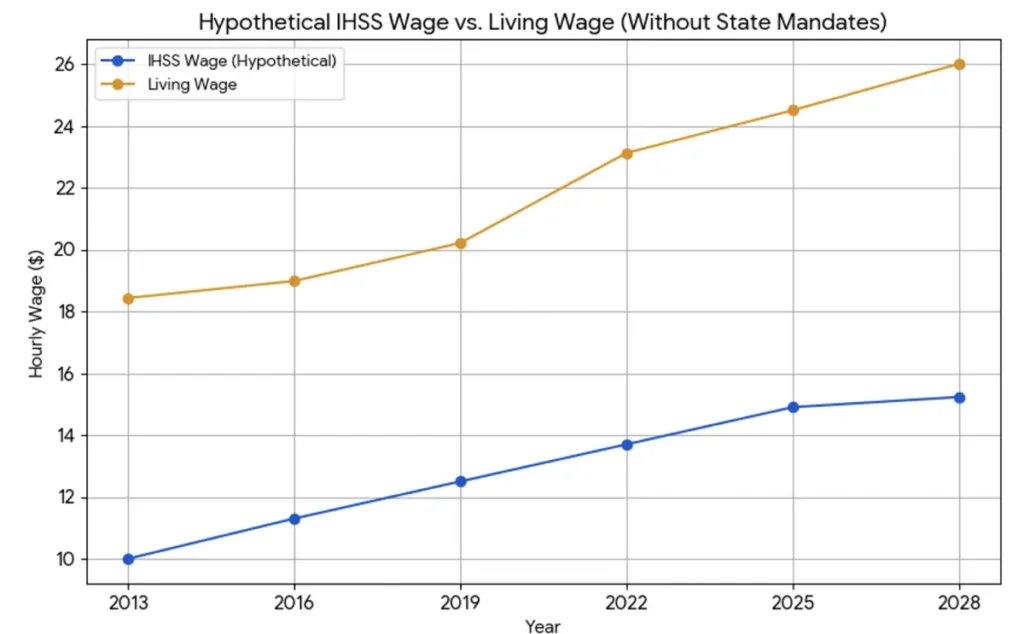

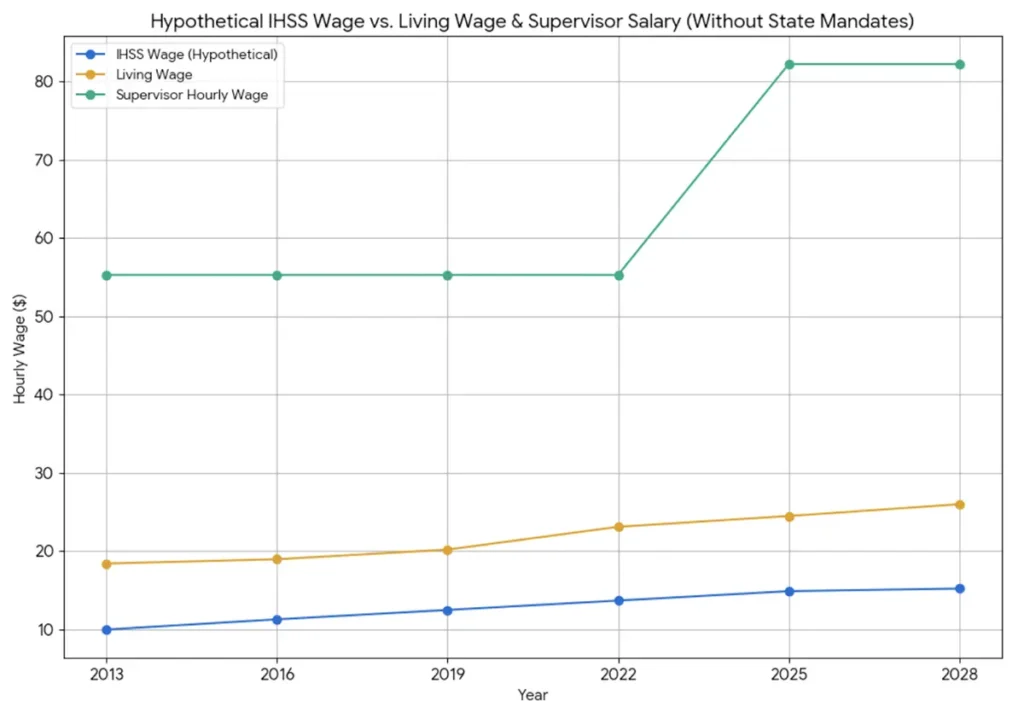

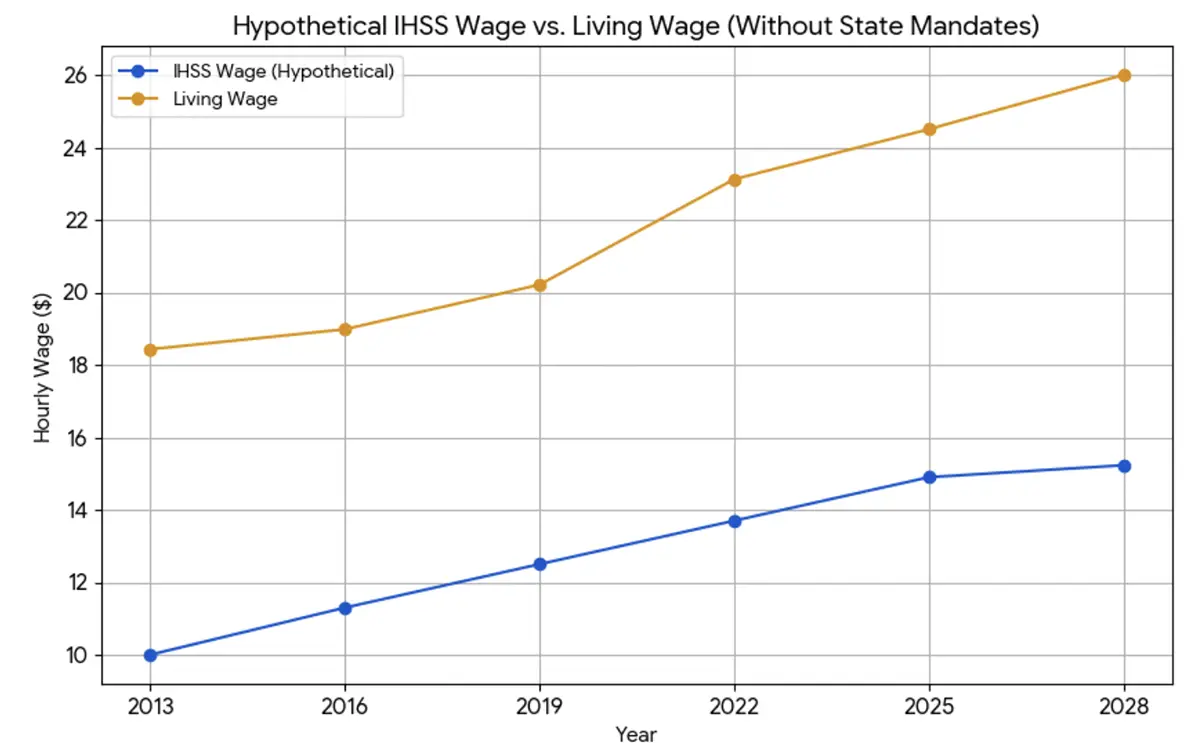

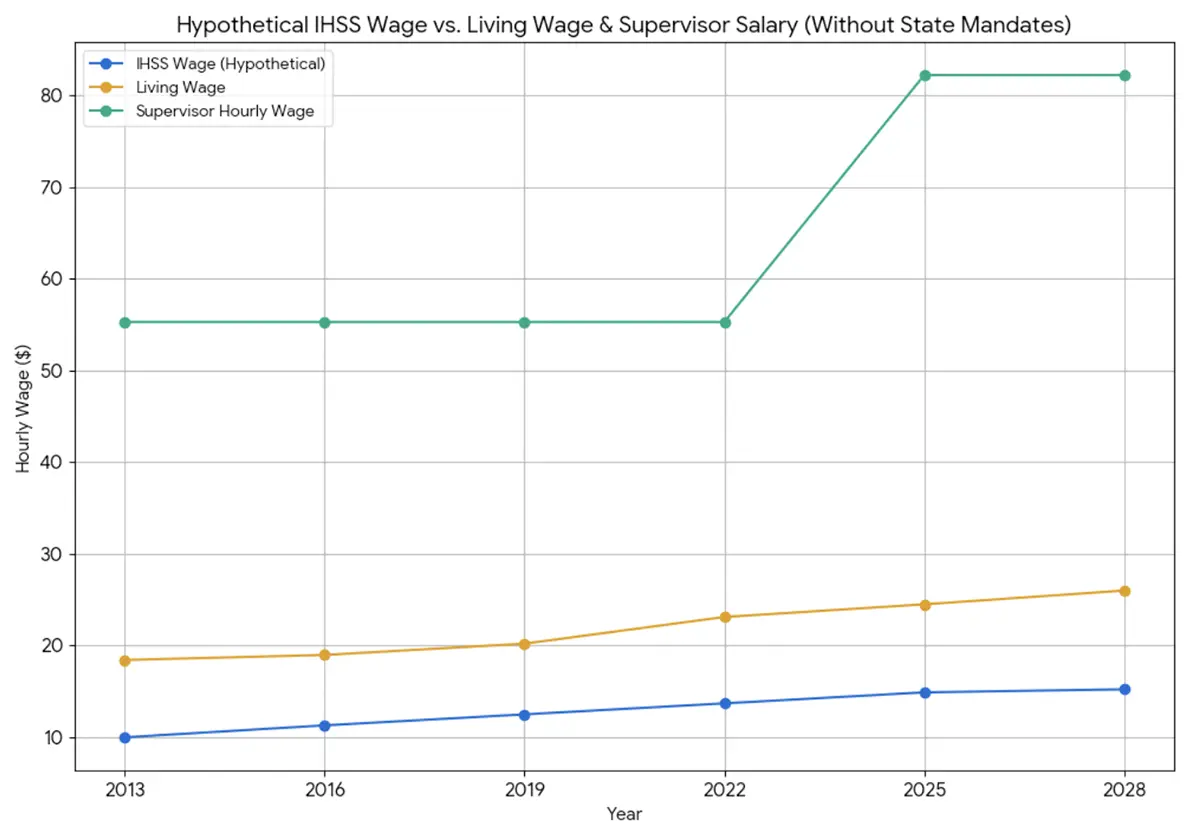

Chart 2: The Hypothetical Timeline

This second chart removes the state-mandated minimum wage increases and illustrates what our pay would be if it had only followed the county’s own historical pattern of raises. This shows the true nature of the county’s commitment to its caregivers.

- A Constant Decline: Without state intervention, our wages would have been in a state of consistent decline against the cost of living for over a decade.

- The Lowest Point: Your proposed 33-cent raise, when viewed in this context, would not only be insufficient but would lead our purchasing power to its lowest point in history, falling to just 54% of the living wage.

The conclusion from these charts is undeniable: The proposed contract is not a solution—it is a continuation of a decades-long trend of bleeding IHSS caregivers dry. We provide compassionate, life-sustaining care that saves the county millions of dollars. In return, we have been offered a wage that ensures we fall further and further behind, while your own salaries soar.

Just out of curiosity, I rendered one more chart.

Do you see the disparity?

I urge you to look at the data in these charts and reconsider your priorities. A living wage is not a request for a handout; it is a demand for a fair and just system that values the essential care we provide.

A Loved One's Choice: The Critical Difference Between Home and Institutional Care

Home Care: Studies and reports highlight that in-home care improves quality of life by allowing individuals to remain in a familiar and comfortable environment, promoting independence, preserving routines, and reducing stress. The ability to make personal choices—like what to eat, when to go out, and who to socialize with—is a key benefit.

Institutional Care: In contrast, institutional settings are often described as restrictive, regimented, and segregated. They can limit a person’s control over their daily life, privacy, and personal choices, which can negatively impact their sense of self-worth and well-being. Mental Health and Social Interaction:

Home Care: Community-based care fosters social interaction and community integration, helping to reduce feelings of loneliness and isolation. Caregivers often provide companionship and facilitate participation in social activities and community life. The ability to live with family members and maintain existing relationships is a significant mental health benefit.

Institutional Care: While institutional settings can offer opportunities for social interaction with other residents, they often lead to a loss of family relationships and social support from the wider community. A history of institutionalization is linked to higher rates of loneliness and social isolation. Physical Health and Lifespan:

Home Care: The research on mortality risk is mixed and of “very low certainty,” with some studies suggesting an increased risk of hospitalization for individuals in home-based care. However, home care can be personalized to manage a person’s specific needs, which can help prevent some medical complications.

Institutional Care: Institutionalization has been associated with a higher risk of neglect, inhumane conditions, and abuse in some cases. Historically, these settings have led to a higher incidence of chronic conditions due to less access to preventive care. Conclusion:

The ability to live at home and participate in the community is a fundamental right and a key factor in a person’s quality of life. Institutionalization, on the other hand, is often associated with a loss of control, privacy, and social connections, which can be detrimental to an individual’s mental and emotional health. The Department of Justice’s Olmstead ruling and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) both emphasize this right, stating that people with disabilities should receive services in the most integrated setting appropriate to their needs.

I’d like to add a personal note to this. May years ago, I worked at the Porterville Developmental Center, an institutional facility. Twice a year, the staff would know that inspectors were coming, and they’d plan activities with treats and ballons and a petting zoo, etc. As soon a sthe inspectors left, there were no planned activities or engagement with the residents. They were ignored and treated with indifference. After this experience, it is intolerable for me to consider this kind of placement for my son. When I am no longer able to care for him, there will be no options for Tom and I am concerned that this is inevitable. If IHSS wages were higher, maybe Tom would be able to stay at home.

A Review of Elderly and Disabled Care Programs by Country

Ranking of Nations by Comprehensive Care for the Elderly and Disabled

This list ranks developed nations based on the overall comprehensiveness of their long-term and in-home care systems for the elderly and disabled. The top-ranked countries are known for their universal, tax-funded systems that emphasize a person’s right to “age in place” with a wide range of available services.

1. The Netherlands

The Netherlands consistently ranks at the top for its long-term care system. It has one of the highest public spending rates on long-term care as a percentage of its GDP. The system is based on universal, mandatory social insurance, ensuring all citizens have access to care regardless of their income or assets. A key feature is the “Long-Term Care Act” (Wlz), which provides institutional and home-based care for individuals with severe, chronic needs. It also has a strong focus on community care and supporting informal caregivers.

2. Sweden and Norway

The Nordic countries, particularly Sweden and Norway, are renowned for their highly decentralized and comprehensive care models. Care is primarily funded through general taxation and is considered a social right, not a means-tested benefit.

- Sweden: Municipalities are responsible for providing a wide range of services, including home care, day centers, and nursing homes. The system is designed to provide seamless care from hospital to home.

- Norway: The country invests heavily in social welfare and has a decentralized model where municipalities are responsible for primary health services, including home care and nursing homes. Both countries have a strong “aging in place” philosophy, providing significant support to allow people to stay in their homes as long as possible.

3. Germany

Germany operates a mandatory, social-insurance-based system known as “Pflegeversicherung,” or long-term care insurance. This system provides a broad range of benefits, including both cash allowances for family caregivers and direct funding for professional home care services. All workers and employers contribute to this fund, which ensures near-universal coverage and protection against the high costs of care.

4. Japan

Japan’s system is notable for its mandatory long-term care insurance (LTCI) program for all citizens aged 40 and over. This system provides a range of services, including institutional care, home visits, and rehabilitation. It is designed to shift care away from hospitals and families and towards a more formal, organized system. The program is financed by a combination of taxes and premiums.

5. France

France has a hybrid system that combines universal coverage for some care costs with means-tested cash allowances for in-home assistance. It uses a universal solidarity fund to help pay for services, but benefits decrease as a person’s income increases. The system provides for both in-home and institutional care but can place a substantial financial burden on families with higher incomes.

6. United Kingdom

The UK’s system is highly decentralized, with local authorities responsible for assessing and providing care. While the National Health Service (NHS) provides medical care for free, social care for daily living is often means-tested. This means that a person’s assets and income are assessed, and they may be required to pay for a significant portion of their care if they do not meet the low-income threshold, which can vary by locality.

7. The United States (with a focus on California’s IHSS)

The U.S. long-term care system is primarily a means-tested, safety-net model. There is no universal, public long-term care insurance program. Most people must “spend down” their personal savings and assets to qualify for Medicaid, which is the largest public payer for long-term care. Programs like California’s In-Home Supportive Services (IHSS) are a part of this Medicaid system. IHSS is highly beneficial for those who qualify, as it provides funds for personal and chore services to allow individuals to remain in their homes. However, because it is tied to Medicaid, it is not a universal benefit and is only available to low-income individuals who meet strict eligibility criteria. The lack of a nationwide, universal system, coupled with the high cost of private care, places the U.S. at the bottom of this list of developed nations in terms of comprehensive public support for long-term care.

Wouldn’t it be nice to see America higher up this list?

Santa Barbara’s 30-Year Tradition: $10 Below Survival and growing

For nearly 30 years, IHSS caregivers in Santa Barbara County have been told to wait, to sacrifice, to accept less. At our very best, we’ve reached only 64% of the living wage — and even that was not because of county leadership, but because the state raised the minimum wage and forced your hand. That is not progress. It is entrenching caregivers in permanent poverty.

We are not asking you to erase the $10 gap overnight. But the truth is, it’s not a one-time shortfall. For nearly 30 years, the County has kept IHSS wages pinned within a dollar or two of being $10 below the living wage — a pattern that cannot be explained as coincidence. We are asking for a plan — a roadmap that shows caregivers moving forward instead of slipping backward.

Right now, caregivers are slipping backward in every way:

Families are broke. Most of us live paycheck to paycheck, with no way to save for emergencies, retirement, or even next month’s rent.

Housing is unstable. Caregivers are being priced out of Santa Barbara, forced to choose between leaving their communities or losing the people they care for.

Health is sacrificed. Many caregivers skip their own medical care and medications because there is nothing left after covering the basics.

The system will collapse. If caregivers can’t afford to stay in this work, clients will be pushed into costly institutions — the very outcome IHSS was designed to prevent.

This is the reality of “business as usual.” Without a plan to close the gap, you are not just underpaying workers — you are putting families, clients, and the entire program at risk.

Caregivers deserve more than survival. We deserve dignity, security, and a future where our work is valued. Anything less is exploitation.